Post-Mortem: Impossible Landscapes in Fate

8/24-3/25; 16 Sessions

In my junior year of high school, I promised a friend that I would run Call of Cthulhu. Instead, I turned right around and ran a pulp sci-fi campaign instead. When the pandemic hit, that same friend and I passed time watching True Detective on a Discord call. Come freshman year of college, we shared a dorm and spent our nights watching the X-Files. We’d move into a house together a year later, and there made a weekly habit of cooking pancakes and watching Twin Peaks. When I finally moved out into a studio apartment, we still got on call to watch Kolchak. Ultimately, this campaign is dedicated to my roommate, and to our shared love of supernatural procedurals. At the cusp of 22, it’s time to fulfill the promise of my 17-year-old self.

Structure

Given our media diet, the first certainty was that the campaign would take place in the Delta Green setting. So I sent out the following pitch:

“Deception is a right. Truth is a privilege. Innocence is a luxury.”

It’s easy to forget Delta Green. That’s the point. Months spent typing away at a keyboard in an alphabet agency and the bureaucratic mundanity begins to take on some semblance of import. The home takes on some semblance of sanctuary. Coffee that tastes bad still satisfies in its ritual regularity. But then a dossier lands on your desk, an inter-departmental meeting is arranged, and you spot your cell-mates. And you recognize the look on their faces, violently awoken from pleasant slumber.

You are the Agent of a covert group embedded inside the U.S. government. Its mission is erasure. Destroy, capture, contain, or conceal, in that order. Your target? The cosmically unjust. That which expresses total disregard for man and his imagined law. Your body and mind will stand between the collective Homo-Ego and the entropic force of reality. You will stand tall because there is a fire burning, and the slightest wind could blow it out. Because you are afraid of the dark. You will lie. To others, certainly, but mostly to yourself. And in the small hours, tossing about your motel mattress, you forget if you’re waking up or falling asleep.

The second, probably controversial, certainty was that we would be using the Fate Core RPG system. I’ll discuss this choice in greater detail later, but in short, I was suspicious of how well Delta Green’s more lethal ruleset would support character-focused campaign play. Fate, on the other hand, aligned remarkably well my emerging RPG philosophy.

Loosely following Fate’s Game Creation procedure, the whole group sat down for a session zero, and we worked out the campaign to come based on this slideshow. Not yet familiar with Fate’s more improvisational campaign style, I came to the table with a few potential modules in mind. My players were most interested in exploring the tensions of fate vs. free will and rationality vs. irrationality, so I settled on running Impossible Landscapes.

Story

What is Impossible Landscapes about? This question has gathered a large amount of speculation online, particularly from those who have read but not run it. Standing on the other side of it now, I would say it is best described by its own creator as being “designed to produce a particular set of feelings in the Agents who play it.” It is, more than any other campaign I’ve run, experiential. I found myself learning more about the story alongside the players as we pursued it to its hiding places.

Still, to get the most out of IL the GM needs to be a few steps ahead of the curve. I would say reading Chambers’ King in Yellow stories in their entirety is a necessity. “The Repairer of Reputations", “The Mask”, and “The Street of the First Shell” introduce characters, themes, and settings core to Impossible Landscapes and without them a tremendous amount of meaning is lost. In fact, “The Mask” encapsulates the heart of IL in a single sentence, “The mask of self-deception was no longer a mask for me, it was a part of me.”

My cast consisted of four agents: Lucy Woods, an orphanage volunteer and IRS accountant plagued by unaccountable coincidences; Igor Mort, a powder-keg medical examiner recently diagnosed with brain cancer; Elijah Carter, who abandoned his cultish Christian hometown to become a poster boy for the FBI; and Edward Armstrong (the player to whom this campaign is dedicated), an anthropologist whose obsession with the occult recently surpassed his care for ethics.

As the campaign progressed, each character began to don a mask. Ms. Woods, finding her name on a family tree charting the “Imperial Dynasty of America”, began to attribute a significance to her bloodline, and to the many coincidences of her life. Dr. Mort, discovering a golden beetle, noticed its striking similarity to the lump shown by his MRI scans. Professor Armstrong, upon reading the pages of a play, begins to suspect himself a character who wandered far afield of the stage. I would say most satisfying of all, however, was the case of Agent Carter, whose relationship with his deeply religious brother Jonathon had been deteriorating ever since he left Jon behind to pursue his career.

Between the first and second chapters of the campaign, I introduced the church Jon attended: The Sowers, and its minister Mark Brand. Brand had encountered the King in Yellow as the sacrificial lamb Azazel. In this form, the King allowed Brand to don the mask of innocence, causing all around to forget his transgressions. Eventually Brand himself forgot he ever had a reason for humility. Knowing he could escape any consequence, Brand grew bold, expanding his Church, killing those who threatened his machinations, and allowing those most faithful to meet his newfound patron. When the Agents became involved, Elijah’s brother was thrust squarely in the crossfire, and that early abandonment, those years of neglect, led to a bitterness which made Jon an enemy rather than an ally. When a Delta Green kill squad finally came to raze the Sower’s compound to the ground, Elijah abandoned Jon for the last time.

The death of his brother forced Elijah to confront a guilt which spanned all the way back to his childhood. Elijah increasingly felt the need for some form of absolution, and that was when Azazel revealed himself to him.

The world around the characters takes on their fancies, until the very term “reality” loses its meaning. They receive invitations to a masquerade in the “fictional” city of Yhtill. All approach, at first reluctantly, then desperately toward the end of the beginning of the end. Along the way, Armstrong relinquishes his invitation, and thus his character, to the enigmatic Mr. Wilde. The remaining Agents uncork ancient bottles blown specially for them and I ask each player to answer the question at the heart of their character: Does Lucy return to her adopted family in the “real world” knowing she is nothing but a pawn upon the strings of fate, or does she choose the autonomy, authority even, granted by the royal blood of Yhtill. Does a tumor drain Mort’s life away while his loved ones sit at bedside, or does a Gold Bug mark him as the chosen of the demon Stolas, alone but alive in Carcosa? Does Carter admit his failure to save his brother, or does he erase Jon from memory, accepting that self-deceiving innocence as truth.

The highest compliment paid to this campaign was that every player chose fantasy over fact. Midnight arrives, and that which was once Armstrong now enters a Stranger bearing only a pallid mask. We see the opening sequence of the campaign again, with fresh actors playing the Federal Agents, and Steely Dan’s “Do It Again” rolls us into the credits.

System

Of course, in my recounting of events I have tidied up our game and made it appear more neat than it really was. Not only is Impossible Landscapes a campaign unlike any other, but Fate is a system unlike any other, and it was our first time with both.

In addition to the usual awkwardness of learning new rules, I began to notice a fundamental incompatibility between Fate and mysteries. A mystery, especially one depending upon the surprise of surreal horror, needs the GM to know things in advance that the players do not. Fate, on the other hand, requires the players to more or less know everything the GM does. Take consequences, for example. The Fate rulebook explicitly tells the GM to have players help come up with consequences, but when the players don’t know the rules of the world or the conventions of the genre, they cannot provide any meaningful input. As a result, more consequences end up being bland because the GM is forced shoulder sole creative responsibility.

Fate also mechanizes story progression. In a more traditional roleplaying game, the GM has exclusive power to wall-off or introduce content without interfacing with any mechanics. Setting elements exist prior to the characters encountering them. In Fate, there are specific mechanical procedures for generating setting elements as they are encountered which both the GM and players have access to. With this change, the GM loses much of their power to direct the characters and narrative, which is an incredibly inspiring modality for, say, a sandbox, but rather frustrating for a mystery with a pre-determined end-point.

Then there’s the issue of failure. Fate depends upon failure and success being two sides of the same coin. Both progress the story, just in different ways. When the story needs to go in a certain direction, however, failure becomes much less appetizing to all parties involved, and the mechanics reflecting this philosophy begin to take a back seat to GM fiat.

Still, I don’t know if I would have chosen any other system. Compels, using fate points as positive reinforcement, actually lead to players engaging with the negative aspects of their characters, something which DG/COC’s insanity system fails to do. Fate also escapes the combat-centrism of most RPGs. Heated arguments, terrible realizations, and physical conflicts were all granted similar mechanical weight, each allowed to shine in their own way, and I think this was necessary to facilitate a more cerebral game like Impossible Landscapes.

While I feel conflicted about using Fate to run Impossible Landscapes, I am extremely excited by Fate as a system, and I look forward to using it more as it was intended in the future. For anyone else interested in running or playing Fate, I highly suggest reading the Book of Hanz. It outlines the precise ways in which Fate deviates from most other RPGs.

And so we come to an end of sorts…

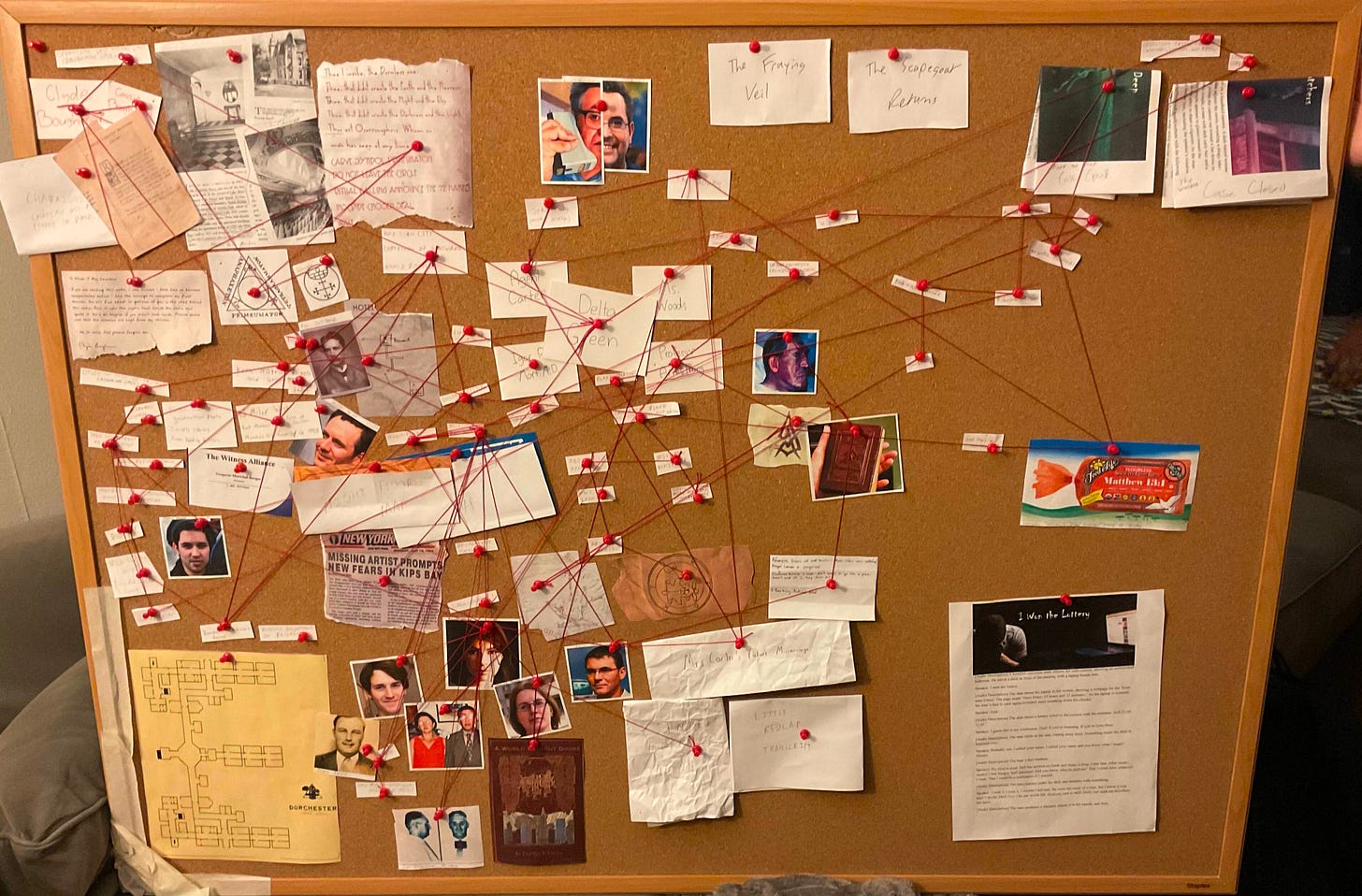

In our post-campaign debrief, Armstrong’s player reports how he spent many mornings examining the party murder board, and many weeknights discussing the mystery at its center. He relates dreams he had of the masquerade and concludes that he, the player, may have been infected by the Yellow Sign in real life. Hearing this, I can finally say that I have properly fulfilled my promise.